Introduction and Related Work

TensorFlow [1, 2] is an open-source dataflow machine learning framework developed by the Google Brain team in 2015. It comprises two stages: the construction of the dataflow graph and the execution of the optimised graph. In their system, a stateful dataflow for machine learning is utilised to store globally mutable variables such as model parameter weights. Additionally, they leveraged device-specific kernel implementations to enable their high-level API to invoke specialised code based on the hardware used by the user, facilitating a single system across any platform. TensorFlow also incorporated several optimisation methods such as automatic differentiation, subexpression elimination, and lossy compression of data to enhance performance during distributed training. Since its open sourcing, it has been widely adopted, with over 1 billion downloads from PyPI [20].

By 2015, machine learning systems needed to address several issues: a deficiency in flexibility to accommodate diverse machine learning algorithms, limited support for heterogeneous hardware due to an initial focus on CPUs, challenges in scaling beyond two nodes, and the necessity for separate systems for training and deployment.

TensorFlow’s predecessor Distbelief [3] was developed based on parameter server architecture [4] but has several limitations [2]. For instance, altering the optimisation method in Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) necessitates modifications to the parameter server architecture. Additionally, the transmission and reception of parameters increase network traffic, which becomes a bottleneck as the model scales. Furthermore, this architecture employs a fixed execution pattern, rendering it unsuitable for training more advanced models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) [11] and Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms [12]. Ultimately, developers concluded that the engineering effort required to refine DistBelief exceeds the benefits of experimenting with new optimization algorithms and model architectures, thus, they opted to proceed with TensorFlow.

Caffe [5], Theano [6], and Torch [7] are single-machine frameworks [1, 2] that focus on executing model training computations on a single computer, thereby lacking mature support for the distributed training of huge models. Conversely, Spark [8] and DryadLINQ [9] are batch dataflow systems [1, 2] that operate on the principle that all input data must be immutable, which renders parameter updates as costly operations.

Approach

Stateful Dataflow with Mutable States for Machine Learning

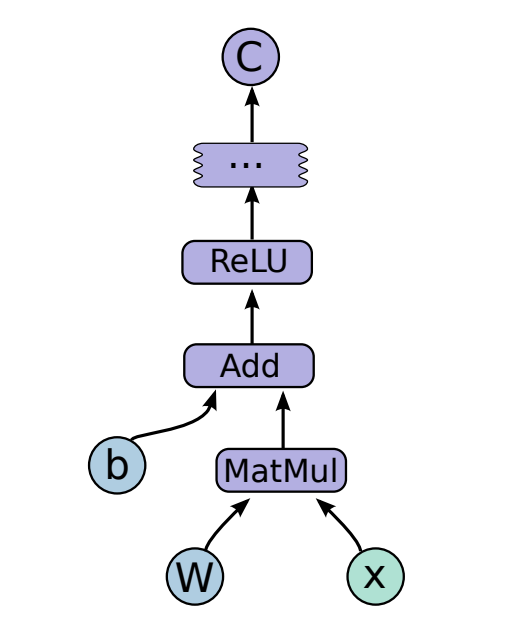

In TensorFlow, individual mathematical operators and model parameters are represented using a dataflow graph, as illustrated in Figure 1. This has allowed users to customise novel layers through their API, facilitating the training of more advanced algorithms such as RNN and RL. Furthermore, TensorFlow supports mutable states that persists across multiple training steps, thereby enabling in-place updates to very large parameters, and enabling experiments with various update rules and optimisation techniques in SGD.

Figure 1: Example TensorFlow computation graph

Figure 1: Example TensorFlow computation graph

Mutable states are supported by stateful operations like Containers, Variables and Queues. A Container is a mechanism that persists until a process terminates, allowing management of longer-lived mutable states such as Variables. Variables possess mutable buffers that can be used to store model parameters during training. Queues are used for producer-consumer coordination, such as managing input data pipeline with backpressure.

Additionally, Tensorflow implemented dynamic control flow by adding if statements and while loops directly into the dataflow graph, allowing for iteration over sequences of different lengths without unrolling the computation to match the longest sequence. This reduces memory overhead and speeds up models with recurrent relations, such as RNN and LSTM.

Single System, Any Platform

TensorFlow has created common abstractions for heterogeneous accelerators, thus able to leverage special-purpose accelerators such as Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) to achieve significant performance improvements. TensorFlow also defines a set of kernels available for execution through a device registration mechanism. As a result, each operator in the dataflow graph can have multiple specialised kernels for different devices, thus the same program can easily target GPUs, TPUs, or even mobile CPUs for its execution.

Furthermore, each specialised kernel can utilise its domain knowledge to accelerate the operator. For example, the use of XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra) [13] for kernel fusion and tiling in matrix multiplication. Specialised kernels can also optimise memory management and communication through RDMA with Infiniband and direct GPU-to-GPU transfer with NVLink.

Distributed Training on Very Large Model

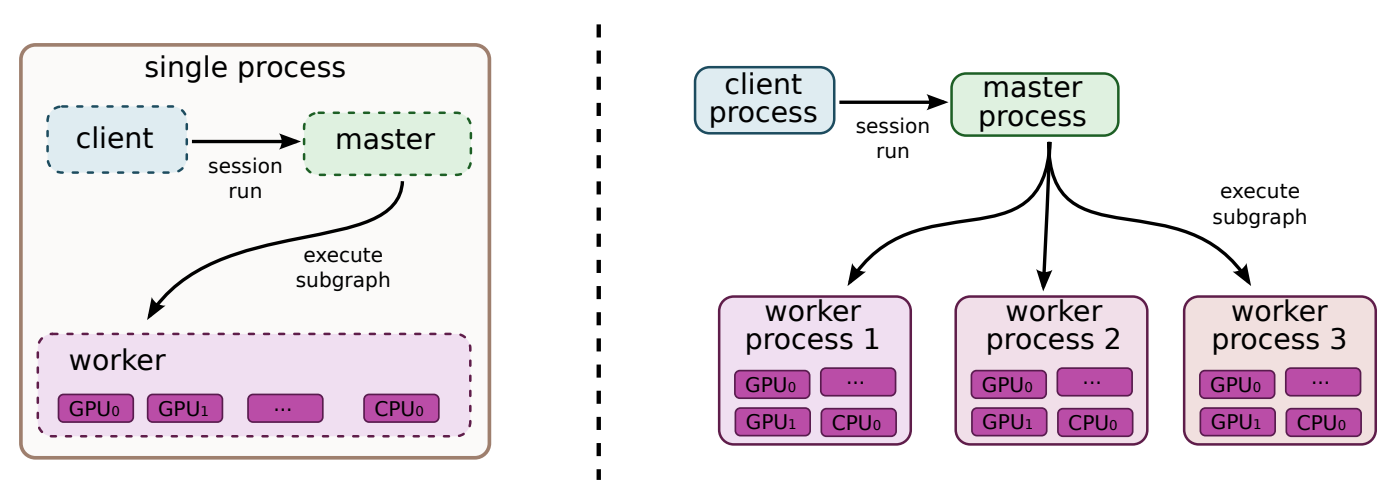

To achieve distributed training on a very large model as shown in Figure 2, TensorFlow built a cost model to decide which device to place the computation for each node in the graph. Then, the placement algorithm runs a simulated execution of the graph, and picks devices for each node using greedy heuristics that take estimated execution time into account.

Figure 2: Single machine and distributed system structure

Figure 2: Single machine and distributed system structure

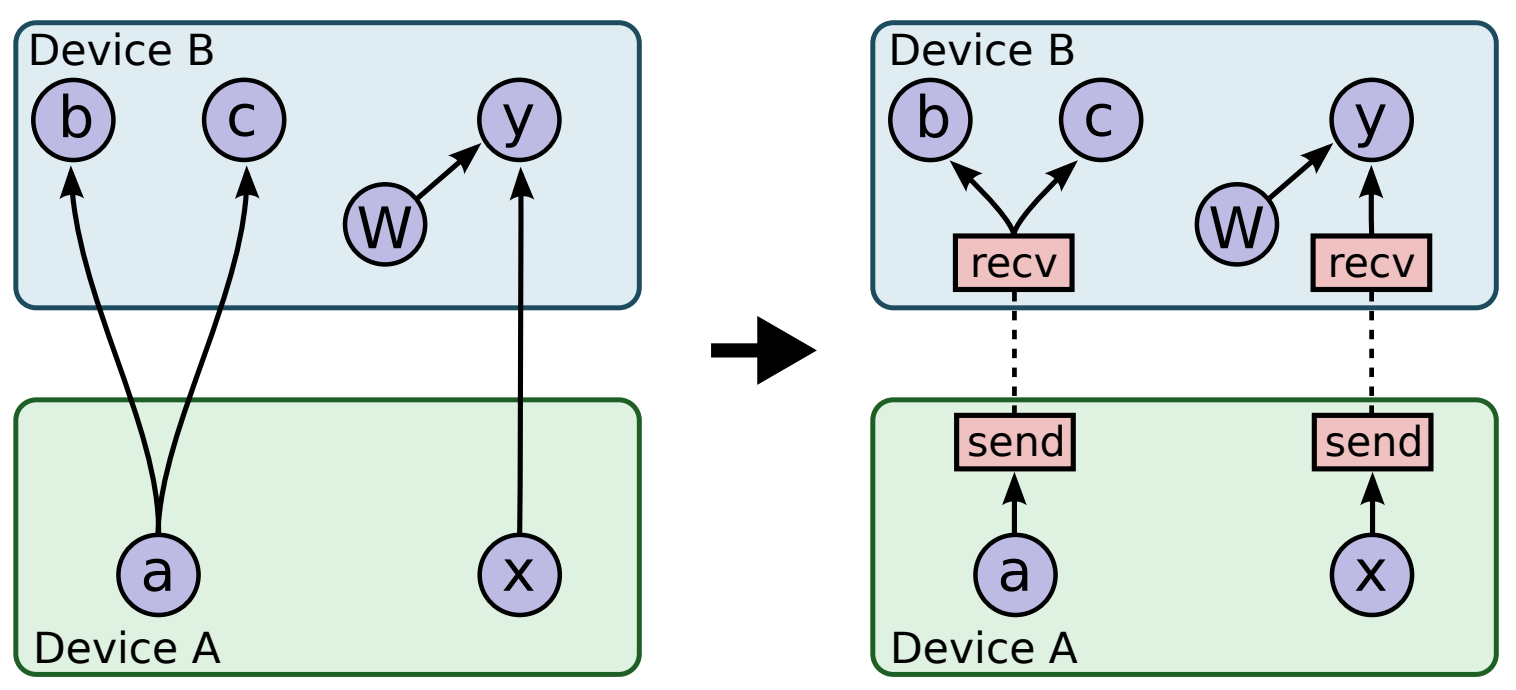

Implied by these placement decisions, during runtime, TensorFlow manages the required communication of data across device boundaries using Send and Receive nodes. By handling communication in a one-to-one manner, TensorFlow avoids the master process being involved in the scheduling of every cross-device communication, thus making the system more scalable.

Figure 3: Before and after insertion of Send/Receive nodes

Figure 3: Before and after insertion of Send/Receive nodes

Furthermore, TensorFlow incorporates native capabilities for automatic differentiation. In this process, TensorFlow autonomously integrates the subgraph responsible for gradient computation into the dataflow graph, then enabling parallel gradient calculations across device partitions. Additionally, partial execution has been enabled to facilitate the execution of specific subgraphs within the entire computational graph, improving efficiency. It also simplifies debugging processes by allowing users to inject arbitrary data and inspect output.

Various Optimisations to improve Performance

In TensorFlow, code for training and deployment is unified, eliminating the need for inefficient code rewriting. Additionally, various optimisations are applied after compiling the dataflow graph. For example, subexpression elimination removes redundant operations, careful scheduling by analysing the critical path reduces the peak memory size of intermediate results, the use of optimised libraries such as cuBLAS [19] and cuDNN [14] improves memory usage and thread coalescing, and lossy compression is used for data transferred across multiple devices.

Evaluation

The authors evaluate TensorFlow along three dimensions: single-machine performance, distributed scalability and large model training.

In single-machine performance, Tensorflow was compared to Caffe, Neon and Torch on four Convolutional Neural Networks (AlexNet, Overfeat, OxfordNet, and GoogleNet) using an Intel Core i7-5930K CPU and NVIDIA Titan X GPU. Tensorflow achieved performance within 6% of Torch on most models, which is no surprise since both uses the latest cuDNN library. Neon outperform TensorFlow on three out of four models due to their hand-optimized convolutional kernel, while Cafee has longer time step compared to TensorFlow.

For distributed scalability, the authors trained Inception-v3 on ImageNet using up to 200 workers on their internal K40 GPUs and a shared data centre network. They achieve a training throughput of 2,300 images per second as the number of workers increased to 200, but with diminishing returns afterwards as contention happens in the aggregation of updates increases. The evaluation also compares synchronous versus asynchronous training, with asynchronous being slightly faster because it does not have to wait for the slowest worker to catch up before starting the next training step. Evaluation also shows that by adding backup workers, TensorFlow reduces the median step time by 9.5%, through mitigating stragglers.

For large model training, the authors evaluated a language model, LSTM-512-512, with a 40,000-word vocabulary on the next word prediction task. Evaluation shows that adding more parameter server tasks increases the throughput, because TensorFlow can exploit model parallelism and distributed softmax computation on the parameter server tasks.

Critical Analysis

Novelty and Strengths

TensorFlow’s key innovation lies in rethinking the programming model from first principles, which involves understanding what Machine Learning needs. Instead of making incremental improvements to their previous system, DistBelief, they took a bold leap by redesigning the entire system.

-

Compared to DistBelief, they abandoned layer-specific design and focused on mathematical operator-specific design, enabling end users to have greater flexibility in customising their neural networks through an easy-to-use API for researchers.

-

Compared to other single-machine frameworks such as Torch and Caffe, they recognised the importance of distributed computing and the trend of training very large language models with millions of parameters, thus shifted their focus towards distributed training by adding send and receive functions for cross-device communication, and enabling flexible parameter sharding to reduce contention.

-

Compared to batch dataflow systems, they challenged traditional dataflow principles of immutable states by designing mutable states suited for Machine Learning applications, making parameter updates a more cost-effective operation.

These visions from TensorFlow and the Google Brain team have laid a robust foundation and enabled researchers to experiment with novel architectures. Subsequently, TensorFlow was used to develop the Transformer architecture [21] in 2017, which became a pivotal design that gained widespread popularity in the years that followed.

Weaknesses

TensorFlow’s most significant weakness, which has resulted in disadvantages for many of its users, is its lack of balance between dataflow programming and eager execution. By concentrating solely on dataflow programming, despite enabling various optimisations that could potentially accelerate training, it has created a steep learning curve for researchers, as the original TensorFlow makes debugging more difficult, thus less user-friendly. In comparison to PyTorch and subsequent frameworks like JAX, it is understood that a process that combines eager execution during development and dataflow programming with optimisation during deployment is essential.

In the evaluation, TensorFlow achieved strong empirical results but suffers from several critical shortcomings that diminish its overall credibility and generalizability.

-

Firstly, they demonstrated scaling limitations. The study showed that scaling beyond 200 workers resulted in diminishing returns due to communication overhead, suggesting that the reliance on simple Send/Receive nodes, rather than collective communication primitives (like NCCL, which the authors noted as future work), was a limitation due to their distributed design.

-

Furthermore, Tensorflow has incomplete comparative analysis. Specifically, they did not compare TensorFlow’s performance to its direct predecessor, DistBelief, or other modern parameter server systems. This makes it impossible for the reader to quantitatively assess the specific architectural gains and benefits of the new dataflow solution over existing ones.

-

Next, their result relies on proprietary infrastructure, making it difficult to validate or reproduce externally. As their results depend on Google’s internal K40 GPUs and shared data centre network, this lack of public reproducibility compromises their credibility.

-

Finally, they didn’t explain the performance anomalies. On single-machine benchmarks, TensorFlow performed within 6% of Torch but did not achieve the same level of performance. While the author claims that the overall similarity is due to the shared cuDNN library, they, however, did not provide any technical explanation for the remaining 6% of performance drop, leaving an important question unanswered.

Future Work

Several areas for future work have been explored by TensorFlow to address its limitations. For example:

-

They incorporate NCCL collective communication, such as AllReduce and Broadcast, that is more efficient than send and receive operations, thereby accelerating synchronous training patterns and enabling tighter coupling of GPU data transfer.

-

They incorporate eager execution and Keras in TensorFlow 2.0 to ease the debugging process for researchers.

-

They developed XLA, a JIT compiler that performs optimisations such as tiling in matrix multiplication, fused operators, instruction reordering, and some other hardware-specific code generation.

While TensorFlow dominated ML frameworks from 2015 to 2018, PyTorch’s eager execution model has gained significant adoption in the research communities. Although TensorFlow 2.0 addressed these issues by making eager execution the default, researchers have been used to the PyTorch framework and have developed their retention. On the other hand, Google’s own JAX framework (2018) has taken a different approach. JAX uses functional transformations such as jit, grad, and vmap on pure Python and Numpy code, thus achieving both ease of use and high performance through XLA compilation. This invention suggests that even TensorFlow’s creators and the Google Team have recognised the need for an alternative programming model.

(Word count: 1800)

References

-

Abadi, M., Agarwal, A., Barham, P., Brevdo, E., Chen, Z., Citro, C., Corrado, G.S., Davis, A., Dean, J., Devin, M., et al. (2016). Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.04467.

-

Abadi, M., Barham, P., Chen, J., Chen, Z., Davis, A., Dean, J., Devin, M., Ghemawat, S., Irving, G., Isard, M., et al. (2016). TensorFlow: a system for Large-Scale machine learning. In 12th USENIX symposium on operating systems design and implementation (OSDI 16), pages 265–283.

-

Dean, J., Corrado, G., Monga, R., Chen, K., Devin, M., Mao, M., Ranzato, M., Senior, A., Tucker, P., Yang, K., et al. (2012). Large scale distributed deep networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 25.

-

Li, M., Zhou, L., Yang, Z., Li, A., Xia, F., Andersen, D.G., Smola, A. (2013). Parameter server for distributed machine learning. In Big learning NIPS workshop, volume 6, number 2. Lake Tahoe, CA.

-

Jia, Y., Shelhamer, E., Donahue, J., Karayev, S., Long, J., Girshick, R., Guadarrama, S., Darrell, T. (2014). Caffe: Convolutional architecture for fast feature embedding. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM international conference on Multimedia, pages 675–678.

-

Al-Rfou, R., Alain, G., Almahairi, A., Angermueller, C., Bahdanau, D., Ballas, N., Bastien, F., Bayer, J., Belikov, A., Belopolsky, A., et al. (2016). Theano: A Python framework for fast computation of mathematical expressions. arXiv e-prints, pages arXiv–1605.

-

Collobert, R., Bengio, S., Mariéthoz, J. (2002). Torch: a modular machine learning software library. Technical Report IDIAP-RR 02-46, IDIAP.

-

Zaharia, M., Chowdhury, M., Franklin, M.J., Shenker, S., Stoica, I. (2010). Spark: Cluster computing with working sets. In 2nd USENIX workshop on hot topics in cloud computing (HotCloud 10).

-

Fetterly, Y.Y.M.I.D., Budiu, M., Erlingsson, Ú., Currey, P.K.G.J. (2009). DryadLINQ: A system for general-purpose distributed data-parallel computing using a high-level language. Proc. LSDS-IR, 8.

-

Medsker, L.R., Jain, L., et al. (2001). Recurrent neural networks. Design and applications, 5(64-67):2.

-

Wiering, M.A., Van Otterlo, M. (2012). Reinforcement learning. Adaptation, learning, and optimization, 12(3):729.

-

Sabne, A. (2020). XLA: Compiling Machine Learning for Peak Performance.

-

Chetlur, S., Woolley, C., Vandermersch, P., Cohen, J., Tran, J., Catanzaro, B., Shelhamer, E. (2014). cudnn: Efficient primitives for deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.0759.

-

NVIDIA Corporation (2025). CUBLAS Library User Guide. NVIDIA Corporation. https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/pdf/CUBLAS_Library.pdf. Accessed: 2025-11-01.

-

Pepy Tech (2025). PyPI Download Statistics for TensorFlow. https://pepy.tech/projects/tensorflow. Accessed: 2025-11-01.

-

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, Ł., Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

-

Paszke, A., Gross, S., Massa, F., Lerer, A., Bradbury, J., Chanan, G., Killeen, T., Lin, Z., Gimelshein, N., Antiga, L., et al. (2019). Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32.

-

Frostig, R., Johnson, M.J., Leary, C. (2019). Compiling machine learning programs via high-level tracing. In SysML conference 2018.