Abstract

Malay language model evaluation currently relies on question-and-answer benchmarks and lacks curated minimal pairs for evaluating language model grammaticality. To address this, we introduce the first Malay-specific minimal-pair dataset for language model evaluation, focusing on two phenomena: Verb Affixation (distinguishing passive prefixes di- and diper-) and Reduplication (ensuring head-noun only pluralisation). Our result reveals that our model achieved high perplexity scores but lower SLOR accuracy. Analysis suggests that the model’s high perplexity scores are confounded by lexical frequency that was previously present in the pretrained dataset.

1. Introduction

Malay Language, the ancient form of Bahasa Indonesia [1], is a context-free grammar with a subject and a predicate [2, 3]. It is widely used and is the national language in countries such as Malaysia, Brunei, and Singapore. Like Bahasa Indonesia, it is an agglutinative language in which a word typically consists of two or more morphemes, each clearly marking its boundaries [4, 5].

As Artificial Intelligence is increasingly applied across industries such as personal chat assistants, legal contract review, and automotive systems, countries like Malaysia have developed their national Malay AI model, such as Ilmu AI. However, there is currently no Malay minimal-pair dataset to evaluate Malay language models’ capabilities, leaving the advancement of Malay AI models solely reliant on question-and-answer benchmarks such as MalayMMLU, without explicit investigation of their grammatical and syntactic capabilities.

In this project, I aim to bridge the gap by creating the first Malay-specific minimal-pair dataset for language model evaluation, thereby enabling AI practitioners in Malaysia to evaluate their models for grammaticality. I sought to examine these two commonly used grammars: Verb Affixation and Reduplication, from the perspective of Tatabahasa Dewan [2], our go-to textbook in linguistic matters. For the experiment, I will use the ASEAN language treebank as the dataset, create the minimal pairs based on technically accurate grammar rules and regex-based template search, then subsequantly evaluate the Goldfish model on the minimal pairs, measure metrics such as perplexity and SLOR, and explain the result using an explainable AI tool such as LIME.

The main contributions of my project are as follows:

- Designed and created the first Malay-specific minimal pair dataset (focus on verb affixation and reduplication) for language model evaluation. All the code is reusable, and open-sourced at https://github.com/woonyee28/L95-Malay-Minimal-Pairs.

- Comparative analysis of the Malay Goldfish model on the dataset based on SLOR and perplexity. Result revealed that Goldfish achieved 90.40% perplexity and 74.60% SLOR accuracy in affixation, and 94.00% perplexity and 88.10% SLOR accuracy in reduplication.

- Our analysis shows that SLOR is a more reliable metric for assessing grammatical knowledge by mitigating the lexical frequency that confounds the perplexity measure.

2. Grammatical Phenomena in Malay

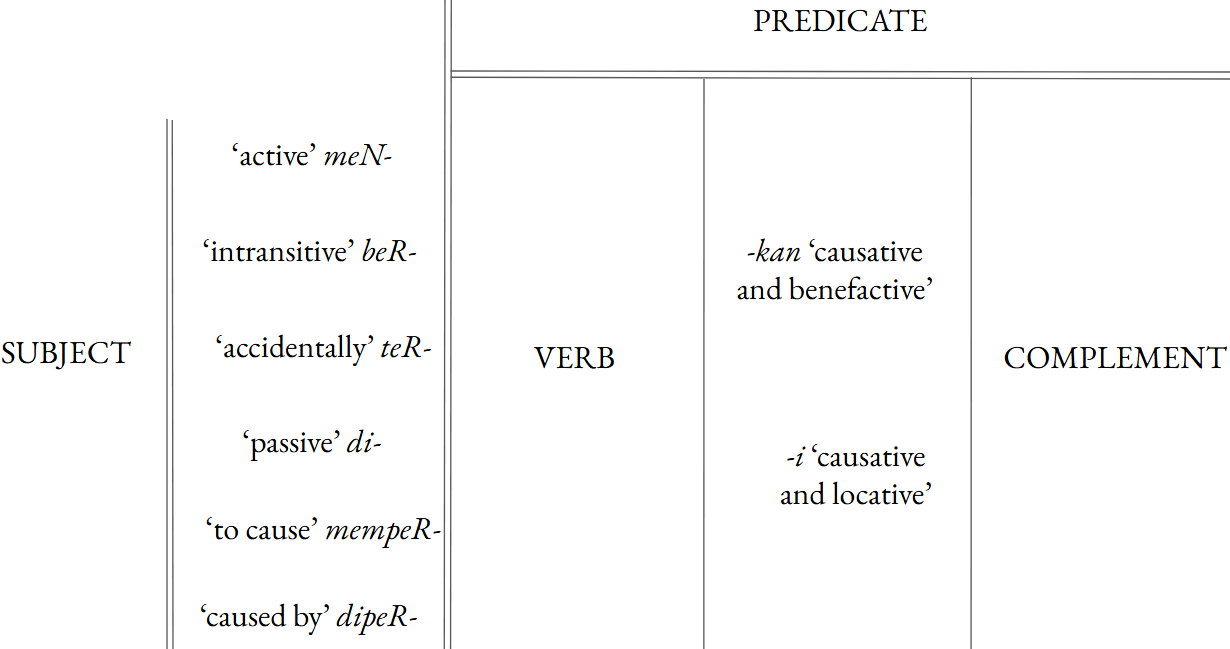

Figure 1: Standard Malay verbal affixes. Graphic inspired by [6] and validated through [2]

Figure 1: Standard Malay verbal affixes. Graphic inspired by [6] and validated through [2]

2.1 Verb Affixation

Semantically, context was injected into a verb through affixation in Malay. According to Tatabahasa Dewan [2], there are six common prefixes: meN-, ber-, ter-, di-, memper- and diper- and two common suffixes: -kan, -i, as shown in Figure 1. A common way for native Malay speakers to explain meN- is to use the English progressive marker be …-ing as an example [7]. Like be …ing, meN- in Malay indicates action in progress in the active voice. On the contrary, di- is the manifestation of passive voice just like to be + past principle in English. For prefix beR-, its primary function is to form an intransitive verb, expressing an action that stems from the original meaning of the root. For example, kasut is a noun meaning “shoes,” and berkasut means “to wear shoes.” For the prefix ter-, it indicates accidental or unintentional action. For memper- and diper-, the additional -per- cannot exist without mem- or di-. It is causative, and it indicates three types of extra meaning: use [something] as a metaphor, to amplify [something] or to acquire [something]. For example, in the case of metaphor, alat means “tool”, and memperalat means “to use or exploit someone or something as a tool”. In the case of amplification, it is used together with an adjective, where, for instance, besar is “big”, diperbesar means “made bigger”. For -kan and -i, they were used to determine the semantic relationship between the verb and complement, -kan introduces a benefactive argument, whereas -i introduces a locative argument."

For first set of Minimal Pair, I have selected di- and diper- as the grammatical rules to manipulate, as the distinction between them is subtle and often confuses both adult learners and native speakers. In practice, these two are generally not interchangeable in Malay as di- marks the simple passive voice and diper- marks the causative passive voice. For example, diperbesar means “made bigger”, and *dibesar is ungrammatical unless you add a -kan as a suffix, which alters the semantic meaning into “to be raised/brought up”.

2.2 Reduplication

| Word Class | Maintenance of Word Class | Change of Word Class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Reduplicated | |

| Nouns | orang ‘person’ | orang-orang ‘people’ | hati ‘heart’ | hati-hati ’to take care' |

| budak ‘child’ | budak-budak ‘children’ | mata ’eye' | mata-mata ‘police’ | |

| Verbs | makan ’eat' | makan-makan ’eat lightly' | masak ‘cook’ | masak-masak ‘mature’ |

| minum ‘drink’ | minum-minum ‘drink leisurely’ | kira ‘count’ | kira-kira ‘an estimate’ | |

| Adjectives | merah ‘red’ | merah-merah ‘very red’ | cepat ‘fast’ | cepat-cepat ’to hasten' |

| putih ‘white’ | putih-putih ‘very white’ | lambat ‘slow’ | lambat-lambat ’to be slow' |

Table 1: Full reduplication in Malay Language

Reduplication is often used in Malay to indicate the plural form of a word, but its occurrence can also change the word class. There are three significant categories of reduplication: full reduplication, rhythmic reduplication, and partial reduplication [2, 8, 9]. Full reduplication is illustrated in Table 1, which shows instances of word-class maintenance and instances of changes in word meaning due to reduplication. When I was a child, one example of a word class change that I often find fascinating is that mata means “eye” in Malay, but mata-mata became “police”. On top of that, rhythmic reduplication is when the replicated word is similar but not identical. For example, sayur means “vegetable”, and its plural form is sayur-mayur, in which the second word has a slight change of consonant. And partial reduplication is a reduplicative pattern that avoids the repetition of exact or long sound sequences of the same kind [10]. For example, laki means “man”, and lelaki means “men”.

However, reduplication is not without constraints. There are two critical grammatical rules mentioned in [2, 11]. Firstly, when a noun is in its plural form and there is an adjective attached to it, the noun is the word that should be reduplicated, but not the adjective. For instance, the plural of buku is buku-buku and tebal means thick. To describe books as thick in Malay, the plural is buku-buku tebal, not buku tebal-tebal. Furthermore, in a compound noun, only the head noun can be reduplicated for pluralisation, but not the modifier. For example, buku sejarah “history book” becomes buku-buku sejarah “history books”, not *buku sejarah-sejarah.

The above reduplication grammatical rules are selected as my second set of Minimal Pairs. This is because reduplication is less common in English than in Malay and is not covered by popular Minimal Pair benchmarks such as BLiMP [12]. By extending evaluation to reduplication, we are able to evaluate Malay Language models in a morphological phenomenon unique to Malay. In summary, our minimal pair are encouraged by the following grammatical phenomena:

Minimal Pairs Summary

- Verb Affixation: The distinction between the passive prefixes di- and diper-.

- Reduplication: Head noun-only reduplication in adjective-noun phrases and compound nouns.

3. Experimental Method

3.1 ASEAN Language Treebank

For our experiment, we start by searching the available Malay Treebank. Current popular resources, such as Universal Dependency [13], unfortunately, do not include Malay. Fortunately, the Asian Language Treebank (ALT) [14, 15, 16], project created by National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, Japan has included Malay in its open-sourced dataset. The process of building ALT began with sampling approximately 20,000 sentences from English Wikinews, which were then translated into other languages, such as Malay. However, the website tool used to extract the constituent tree is proprietary software to which I have no access. Hence, I sought a Malaysian-based software project [17] that supports the extraction of constituent trees.

3.2 Minimal Pairs Creation

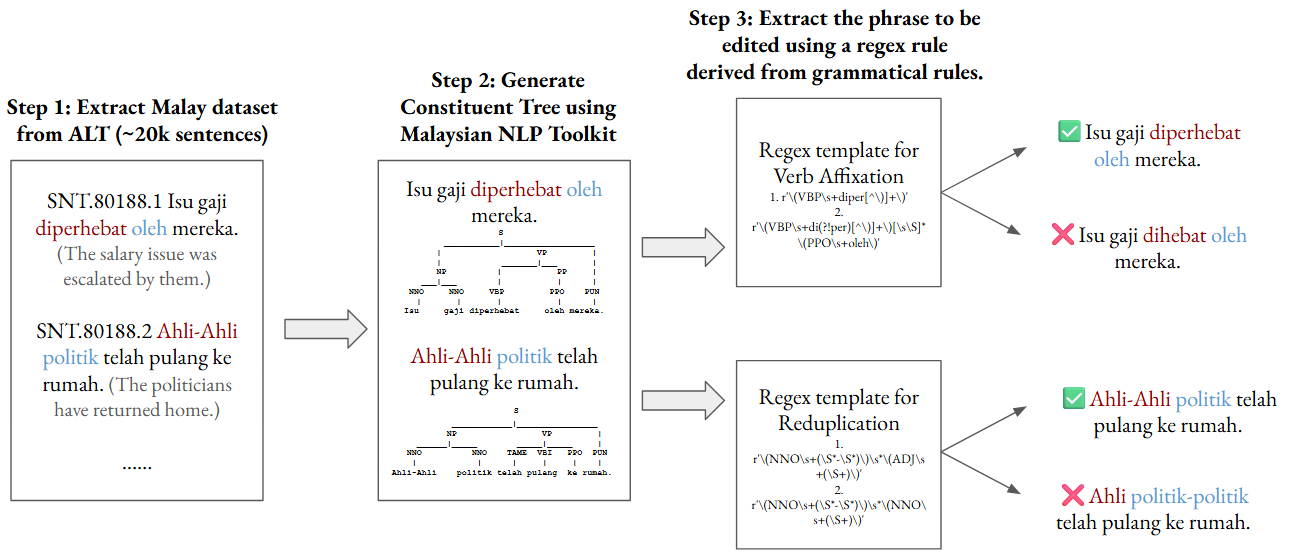

Figure 2: Minimal Pair Generation Process in this project.

Figure 2: Minimal Pair Generation Process in this project.

In minimal pairs creation, we follow the following design principles: (1) Ensure the grammatical and ungrammatical sentence length is the same, and (2) Ensure the minimal edit position is guided by the template search on the constituent trees using regex. After identifying the grammatical phenomena, we use regular expressions to translate the rules into patterns.

For the first set of minimal pairs, we are targeting the distinction between passive prefixes di- and diper-. The tag for passive verb in the constituent tree is VBP. In the experiment, we are testing both directions of change: diper- → di- and di- → diper-. First, we identify the diper- form, extract it, and replace it with di. This will produce ungrammatical sentences in which -per- is obligatory. Secondly, we will identify the di-… form followed by oleh (the passive agent marker) and create an ungrammatical or semantically unacceptable sentence by modifying it into diper-. This tests whether the model recognised the approapriate use of -per- in causative passive construction, as mentioned in [2]

For the second set of minimal pairs, we are ensuring that only the head noun is reduplicated in adjective noun phrases and compound nouns. To search for reduplicated noun-adjective pairs, we use regex to search for NNO & ADJ tags as they represent numeral nouns and adjectives, respectively. For compound nouns, we search for NNO & NNO tags that present side by side. Then, we create ungrammatical pairs by shifting reduplication from head noun to the modifier.

After collecting sentences that fulfil these requirements, we created a total of 1000 minimal pairs for each grammatical phenomenon. Detailed breakdown is illustrated in Table 2.

| Phenomenon | Sub-scenario | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Verb Affixation | di- → diper- | 586 |

| diper- → di- | 414 | |

| Subtotal | 1000 | |

| Reduplication | Compound Noun | 737 |

| Adjective-Noun | 263 | |

| Subtotal | 1000 | |

| Total | 2000 |

Table 2: Summary of minimal pairs created

3.3 Model Used

We use the Malay Language Model developed in the Goldfish series [18]. The specific model is a GPT-2 Transformer 125MB language model trained from scratch on 1000MB of Malay Dataset. The tokenisation process is performed using a monolingual SentencePiece tokeniser [19].

3.4 Evaluation Criteria

We evaluate our model performance on the minimal pairs using two metrics: perplexity and SLOR [20].

Perplexity (PPL) is defined as the exponentiated average negative log-likelihood of a sentence:

$$\text{PPL}(s) = \exp\left(-\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N}\log P(s)\right)$$

where $N$ is the number of tokens and $s$ is the sentence. PPL measures the model’s confidence in the sentence. The higher the PPL score, the lower the confidence, the lower the PPL score, the higher the confidence. We use PPL because it is well-defined for the autoregressive nature of GPT-2 and captures the sequence well. Because PPL exhibits a well-known bias toward longer sequences, we did our best to ensure that our minimal pairs were all the same length.

Additionally, we use SLOR [20] in case our minimal pairs have words with very different frequencies in the pretrained dataset. The main idea of SLOR is to “corrects” the model bias toward frequent words. The calculation is:

$$\text{SLOR}(s) = \frac{\log P(s) - \log P_u(s)}{|s|}$$

where $$\log P_u(s) = \sum_{i=1}^{N}\log P_u(w_i)$$ is the sum of unigram log probabilities, and $$P_u(w_i) = \frac{\text{count}(w_i)}{\sum_j \text{count}(w_j)}$$ is the unigram probability of token $$w_i$$. A higher SLOR indicates that the model thinks that the sentence is more acceptable than a unigram baseline.

For each minimal pair in our benchmark that consists of a grammatical and ungrammatical sentence, a prediction is considered correct if the model assigns a lower perplexity score to the grammatical sentence, or equivalently, a higher SLOR score to the grammatical sentence.

3.5 Explainable AI

To investigate cases where the model incorrectly prefers the ungrammatical sentence, we use LIME’s [21] text explainer to quantify the importance of each word in the sentence, thereby understanding the impact of individual words on the SLOR/Perplexity prediction. Lime Text Explainer works by randomly removing words from the original text and observing how the model’s prediction changes. This allows us to identify the most influential word towards the model’s acceptance of a grammatical sentence or an ungrammatical sentence.

While this perturbation-based explainability tool provides model-agnostic insights for our evaluation, its intermediate perturbed inputs may produce syntactically ill-formed or semantically incoherent sentences. Since the model’s behaviour on such unnatural inputs may not reflect its behaviour on well-formed sentences, the resulting word importance estimates of LIME should be interpreted carefully.

4. Experimental Result

| Phenomenon | Perplexity | SLOR |

|---|---|---|

| Affixation | 90.40% | 74.60% |

| Reduplication | 94.00% | 88.10% |

Table 3: Minimal pair evaluation accuracy using goldfish-models/msa_latn_1000mb.

Affixation. Our Goldfish model achieves higher accuracy with perplexity (90.40%) than with SLOR (74.60%) for verb affixation involving di- and diper- prefixes. The substantial drop in SLOR accuracy after factoring out the token-level frequency suggests that the model is less reliable in distinguishing grammatical and ungrammatical affixation in this context. This observation also indicates that the model’s high performance on perplexity is largely confounded by memorising the high-frequency prefix combined with the root word.

Reduplication. A similar pattern emerges for reduplication. Our model achieves a higher perplexity score (94%) than SLOR (88.10%), though the gap is smaller. The higher SLOR accuracy for reduplication compared to affixation suggests that the model has acquired legitimate structural knowledge of reduplication, rather than merely memorising token-level occurrences. This could be due to the predictable sequential nature of recurrence, where the model has learned to expect it (and a hyphen). Nevertheless, perplexity outperforms SLOR, indicating that token frequency continues to affect the evaluation metrics.

These results reveal a vital distinction between learned grammatical rules and token-count memorisation, and how we should choose our evaluation judiciously. The larger perplexity-SLOR gap in affixation compared to reduplication suggests that our model is more dependent on pre-trained dataset token frequency memorisation in affixation, and has acquired reduplication knowledge, potentially due to the sequential structure with hyphen. Overall, we find that SLOR is a more reliable measure because it isolates the impact of frequency and provides a more accurate assessment of whether the model has learned the affixation rules.

5. Result Analysis

5.1 Affixation

| Pattern | Perplexity | SLOR |

|---|---|---|

| di-→diper- | 94.11% | 70.58% |

| diper-→di- | 83.08% | 82.49% |

| Overall | 90.40% | 74.60% |

Table 4: Affixation minimal pair evaluation accuracy by pattern using goldfish-models/msa_latn_1000mb.

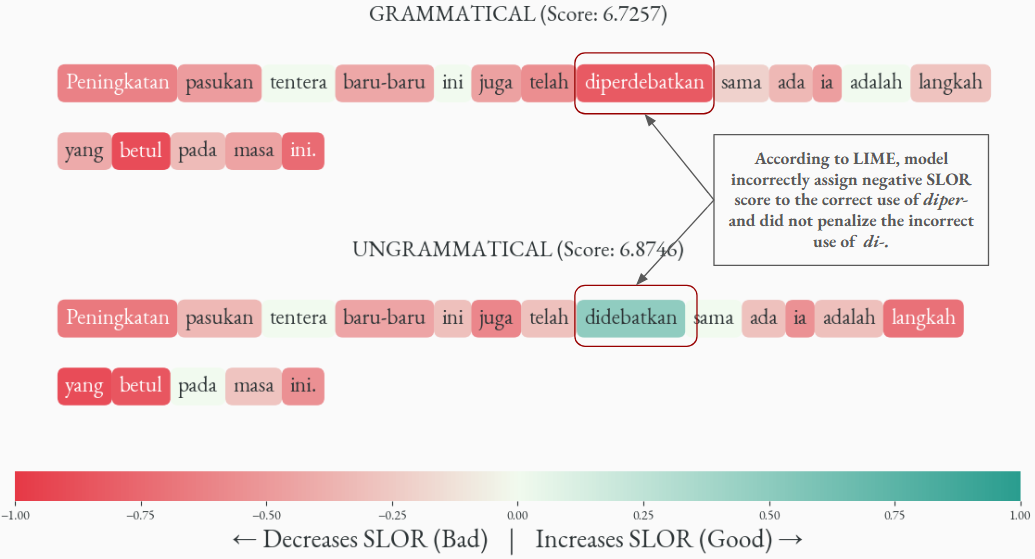

Figure 3: General error trend in Affixation: Model assigns a negative contribution to the grammatically correct diper- form, indicating that this word decreases the sentence’s SLOR score. In contrast, the inappropriate use of di- form receives a positive weight, suggesting the model does not penalise this inappropriate usage. This reveals that the model has learned a preference for the more frequent di- prefix, failing to recognise that diper- is grammatically required in this context.

Figure 3: General error trend in Affixation: Model assigns a negative contribution to the grammatically correct diper- form, indicating that this word decreases the sentence’s SLOR score. In contrast, the inappropriate use of di- form receives a positive weight, suggesting the model does not penalise this inappropriate usage. This reveals that the model has learned a preference for the more frequent di- prefix, failing to recognise that diper- is grammatically required in this context.

Under the two patterns in affixation, minimal pairs, Perplexity, and SLOR scores are comparable in identifying ungrammatical sentences for diper-→di-, but Perplexity outperform SLOR significantly for di-→diper-. To investigate commonly misused root words, I also collate a list of the top 5 words with the highest error counts to input into the tokeniser for analysis of segmentation patterns, as shown in Table 5. To my surprise, when I input those top 5 words into the Goldfish tokeniser, it did not segment any of them and instead, it used the full word as a single token. For example, the token for the root word diperuntukkan is _diperuntukkan. This reveals that the model itself did not explicitly learn morphology by segmenting morphemes during tokenisation, but instead relies on implicit parameters to capture the pattern. Besides, di- is more frequantly used in Malay than diper-. Hence, the higher perplexity scores could be confounded by the word frequency in the pre-trained dataset, which also explains why SLOR scores are generally lower than Perplexity in this context.

| Pattern | Root Word | False PPL | False SLOR |

|---|---|---|---|

| diper→di | diperuntukkan | 9 | 5 |

| diperbuat | 5 | 4 | |

| dipertimbangkan | 4 | 9 | |

| dipertandingkan | 3 | 2 | |

| diperlihatkan | 3 | 2 | |

| di→diper | disokong | 2 | 2 |

| dikawal | 1 | 2 | |

| dijalankan | – | 2 | |

| ditoleransi | 1 | 1 | |

| dihentikan | 1 | – |

Table 5: Top 5 words with highest error counts by pattern in affixation minimal pairs. False PPL and false SLOR refer to the number of errors the model made for that specific word using each metric.

To investigate how the Goldfish model assigns importance to each word in determining grammaticality, we apply LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) using SLOR as the scoring function. We use SLOR rather than Perplexity here to reduce the impact of word frequency on the model’s decision of grammaticality. In our experiment, we found that LIME shows a negative contribution for diper- even though it is grammatically correct, and used correctly in the context. On the other hand, in the same example in Figure 3, the model actually prefers the inappropriate usage of di-. Combined with the tokeniser investigation, and since the diper- form is comparatively rare in Malay, as it brings benefactive and causative constructions, these results suggest that the model appears to rely on word frequency rather than on learning the underlying grammatical constraints.

5.2 Reduplication

| Pattern | Perplexity | SLOR |

|---|---|---|

| Adjective-Noun | 97.32% | 95.02% |

| Compound Noun | 92.83% | 85.66% |

| Overall | 94.00% | 88.10% |

Table 6: Affixation minimal pair evaluation accuracy by pattern using goldfish-models/msa_latn_1000mb.

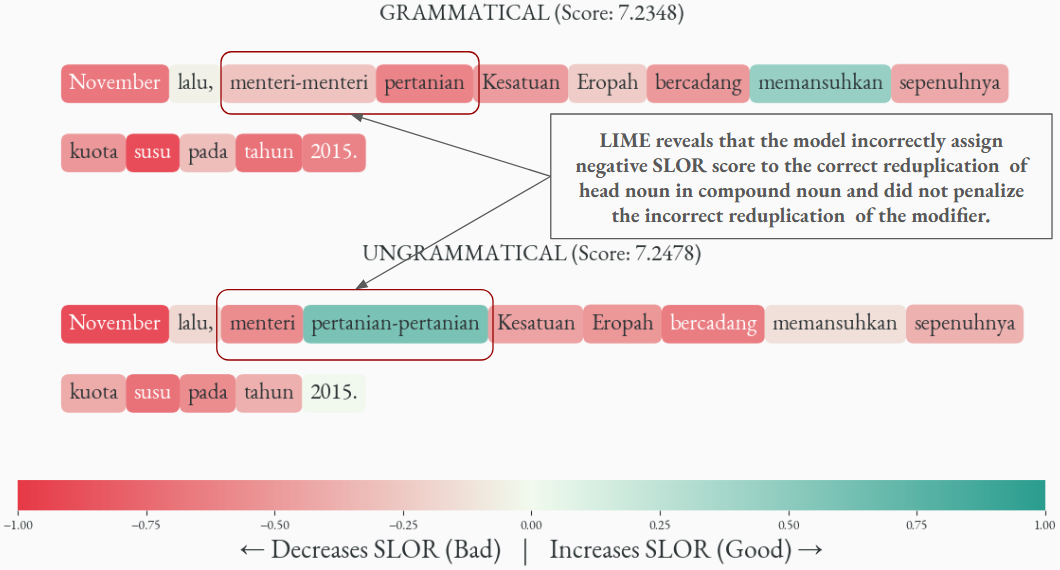

Figure 4: General error trend in Reduplication: LIME analysis reveals that the model incorrectly prefers reduplication of the modifier (menteri pertanian-pertanian) over reduplication of the head noun (menteri-menteri pertanian). This suggests the model lacks semantic knowledge of noun countability in Malay: menteri (minister) is countable and requires reduplication for plurality, whereas pertanian (agriculture) is a mass noun that should not be reduplicated.

Figure 4: General error trend in Reduplication: LIME analysis reveals that the model incorrectly prefers reduplication of the modifier (menteri pertanian-pertanian) over reduplication of the head noun (menteri-menteri pertanian). This suggests the model lacks semantic knowledge of noun countability in Malay: menteri (minister) is countable and requires reduplication for plurality, whereas pertanian (agriculture) is a mass noun that should not be reduplicated.

In reduplication, our Goldfish model performs well on both perplexity and SLOR in adjective-noun constructions, but shows slightly lower SLOR performance than perplexity in compound nouns. In the Malay language, reduplication should be applied to the head noun instead of the modifier. As reduplication of adjectives has fewer variants in Malay, this low-frequency information may not be captured well in the pre-trained dataset, thus, the model performs well on this particular benchmark, as it classifies the low frequency of reduplication of adjectives as ungrammatical, correctly reflecting the lexical frequency. In this case, the words statistics and grammaticality converge, resulting in strong performance, but this doesn’t confirm that the model has learned explicit grammatical knowledge.

To investigate how the Goldfish tokeniser works on reduplication forms, I also filter out the top words with the highest error counts, as shown in Table 7. As a result, I found that the tokeniser will tokenise hyphens. For example, kawasan-kawasan perlindungan will become [’\▁kawasan’, ‘-’, ‘kawasan’, ‘\▁perlindungan’]. Because the hyphen is tokenised separately, the model can learn [word]-[word] as a valid pattern. In fact, the autoregressive nature of GPT2 might also help with the understanding of reduplication. For example, once the model sees [kawansan][-], it can predict the [kawasan] as the next token. However, the model still have to learn the semantic knowledge of which noun is the head noun, to perform well in the minimal pair benchmark.

| Pattern | Root Word | False PPL | False SLOR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjective-Noun | kumpulan-kumpulan subversif | 1 | 1 |

| lebat-udara lembap | 1 | 1 | |

| Dahan-dahan pokok | 1 | 1 | |

| kapal-kalap haram | 1 | 1 | |

| Jenama-tanda baru | 1 | 1 | |

| Compound Noun | kawasan-kawasan perlindungan | 2 | 2 |

| kedua-dua juruterbang | – | 2 | |

| pembeli-pembeli rumah | 1 | – | |

| laporan-laporan masalah | 1 | 1 | |

| ahli-ahli saintis | 1 | 1 |

Table 7: Top 5 words with highest error counts by pattern in reduplication minimal pairs. False PPL and false SLOR refer to the number of errors the model made for that specific word using each metric.

Similarly, we apply LIME to investigate the word importance for the SLOR scoring function. Insight reveals that the Goldfish model incorrectly assigns a negative score to correct reduplication of the head noun, indicating that the model perceives the correct use of grammar as reducing the sentence acceptability. This observation tells that the model does not robustly learned the reduplication rules in terms of adjective-noun and compound-noun, even though their scores in minimal pairs benchmarks are high. Instead, the model still relies on the token lexical frequency in the pre-trained dataset as it is assigning probability, which is understandable as the model training objective of next token prediction relies heavily on the distributional pattern in the dataset rather than explicit grammar rules.

6. Limitation

Scarcity of available Malay Language resources. To the best of my knowledge and research, Malay is not included in Universal Dependency and lacks an official treebank created by the national research agency. Even though I managed to find ALT, the dataset is sourced and translated from English Wikinews, and I have to acknowledge that the translated text may differ from natural Malay usage, as some grammatical constructions might be even more underrepresented. To address this limitation, I attempted to create multiple iterations of regex patterns to capture edge cases and manually verified that minimal pairs incorrectly classified by the model were grammatically sound, drawing on my judgment as a Malay speaker.

Limitations of the Evaluation Metrics. In our evaluation metrics, both perplexity and SLOR are transformations of string probability. However, a recent paper [22] argues that string probability is not the same as grammaticality (which is what we aim to measure), but instead is confounded by two latent variables: message probability and grammaticality. This insight has explained why grammatical but semantically implausible sentences can have low probability, but an ungrammatical sentence with a common message can have higher probability. To address this limitation, we try our best to control the message probability by changing minimally for ungrammatical sentences, ensuring the same exact length is produced, in order to isolate the effect of grammaticality. We also use SLOR in addition to perplexity to subtract the impact of lexical frequency from the scores, aiming to produce a more accurate measurement of the model’s acquisition of grammatical knowledge. This insight also supports my observation that the Goldfish’s model errors may reflect the lexical frequency bias, rather than deciding solely based on true grammatical knowledge.

Limitations of the tokeniser. Our tokeniser is built on the SentencePiece algorithm, and the generated tokens are predominantly whole words rather than smaller morpheme units. This is because SentencePiece optimises subword segmentation based on corpus frequency rather than linguistic morpheme boundaries. As a result, this limits the model’s ability to learn compositional morphological patterns, as a smaller morpheme can encode more interactions and generalise patterns. In my opinion, a language-specific tokeniser should utilise linguistic knowledge to design morphologically informed token boundaries, rather than relying solely on lexical frequency.

7. Conclusion

In this project, I present a Malay minimal pair dataset to help AI practitioners in evaluating their Malay language model. For low-resource linguistic assessment, I recommend that AI practitioners use SLOR, as it provides a more reliable metric for assessing the model’s acquisition of grammatical knowledge.

References

[1] Errington, J. (2006). Indonesian(s) development: On the state of a language of state.

[2] Karim, N. S. (2008). Tatabahasa Dewan.

[3] Ab, A. (2005). Pola ayat bahasa Melayu.

[4] Abdullah, H. (1972). The morphology of Malay.

[5] Tambusai, A. (2016). Morphological analysis of Malay.

[6] Benjamin, G. (2009). Affixes, Austronesian and iconicity in Malay.

[7] Soh, H. L. (2009). The syntax and semantics of the Malay/Indonesian progressive aspect marker.

[8] Nian, S. (2012). A contrastive study of reduplication in Malay and Mandarin.

[9] Alikamal, A. (2012). Reduplication in Malay.

[10] Rubino, C. (2005). Reduplication: Form, function and distribution.

[11] Leong, K. (2023). Bhasa: Malay grammar.

[12] Warstadt, A. et al. (2020). BLiMP: The benchmark of linguistic minimal pairs for English.

[13] Nivre, J. et al. (2020). Universal Dependencies v2.

[14] Lovenia, H. et al. (2024). SEACrowd: A multilingual multimodal data hub.

[15] Thu, Y. K. et al. (2016). Introducing the Asian Language Treebank (ALT).

[16] Riza, H. et al. (2016). Introduction of the Asian Language Treebank.

[17] Malaya. Malaysian NLP toolkit.

[18] Chang, T. A. et al. (2024). Goldfish: Monolingual language models for 350 languages.

[19] Kudo, T. & Richardson, J. (2018). SentencePiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer.

[20] Lau, J. H. et al. (2020). Furiously natural: Measuring grammatical acceptability.

[21] Ribeiro, M. T. et al. (2016). “Why should I trust you?”: Explaining the predictions of any classifier.

[22] Hu, J. et al. (2025). Can language models learn grammatical patterns?